Hierarchy IDs for Fun and Performance

Many systems have a hierarchy in the data. This may be an organisation hierarchy, or maybe a hierarchy caused by a multi-tenant system or a combination thereof.

It’s relatively easy to model a hierarchy in a relational or document database - it is much harder to effectively filter which part of the tree a given user can see or act on. You may find yourself traversing up or down the tree or making multi-table joins.

A simpler solution is to use a Hierarchy ID. In a relational database, you would implement this as a string field with a delimiter-separated list of its parents, for example 120/23/47/19. If a user is allowed to see everything from 120/23 downwards, you can easily search for all the records where the Hierarchy ID starts with 120/23 (indexes will work well with that). In document databases it ma be more optimal to have an array of all the Ancestor IDs instead of a string value.

This post explores the use of Hierarchy IDs to make filtering easy and performant. In addition, it has some pointers about how to set up hierarchical configuration using the same Hierarchy ID you are implementing anyway. Of course, you could just use a graph database and then it’s a different story altogether.

The problem

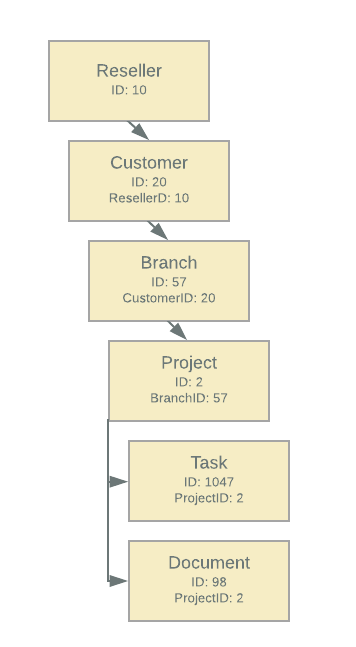

A multi-tenant hierarchy may look like this:

We’ll call this is a fixed hierarchy as it has a fixed depth and different types at different levels.

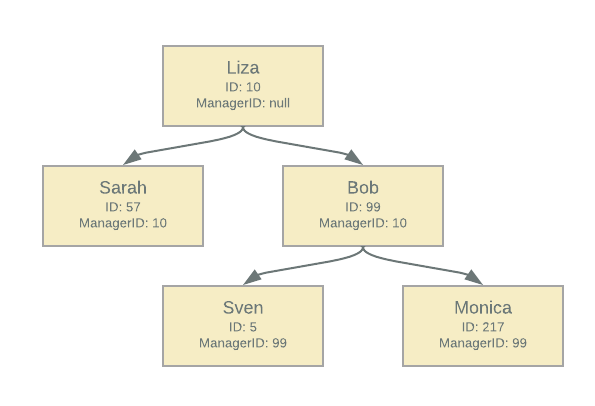

An organisational hierarchy may look like this;

We’ll call this a self-referential hierarchy as each layer in the hierarchy refers to parent/children of the same type.

At NewOrbit we sometimes build multi-tenanted systems which has resellers, who have system customers, who in turn have organisational hierarchies so it can quickly become a very deep hierarchy.

When you are creating your data structure, whether in a relational database such as Azure SQL or a document database such as Mongo or CosmosDb, you will typically have a Parent ID on records in the hierarchy as illustrated above. This is easy at write time and makes it relatively easy to traverse the hierarchy both up and down. However, when you need to get access to a only a part of the tree or indeed multiple subsets of the tree then it becomes very hard to query efficiently and performantly.

As an example with the self-referential hierarchy, imagine in the illustration above that a given user is allowed to see the details of anybody who is in Bob’s hierarchy; you’d need to write a recursive function to keep drilling down the layers until there are no more subordinates. That means running many different SQL queries or using UDFs (which in turn will run a recursive function).

Alternatively in the fixed hierarchy, imagine if a given user has access to see all the projects for three separate branches and they want to see a list of all tasks across all projects they have access to. Or imagine that a Reseller user has access to see all the details for all their Customers, but not for any other Customer - and they want to see a list of all Projects (okay, maybe not the best example in the world, but you get the idea). In that scenario you’d probably write some code that JOINs all the way up the hierarchy and out to various permissions tables, such as “are they in the list that can see the project or in the list that can see the branch or in the list that can see the customer or in the list that can see the reseller”. It may not be that hard to write the code, but it’s easy to end up with a 20-table JOIN, which is expensive on a relational database - and impossible if you use CosmosSB which does not support JOINs.

In this post I am primarily focusing on how to filter the data so a user can only see the data they are allowed in an efficient manner. There are other hierarchy scenarios, in particular around set based operations and there are other patterns that are better suited to those than what I am showing here. I highly recommend Joe Celko’s Trees and Hierarchies in SQL for Smarties for understanding more about this. In fact, the lessons that I am expounding on in this post are based on what I learnt from that book many moons ago. Even if you use a document database, it’s still a good read to understand the patterns.

How to store Hierarchy IDs

As discussed above, you will typically have some kind of Parent ID on each node in the hierarchy (though it’s usually called something more meaningful, such as CustomerID or ManagerID). The trick to efficient querying is to maintain a Hierarchy ID on each record that has all the parent IDs all the way up the tree.

In a relational database, you would store it as a text string like this (for the Task in the fixed hierarchy example above); 10/20/57/2/1047.

In a Document Database you can do the same or use a slightly more efficient approach, which is to store an array of Ancestor IDs. If your documents use GUIDs for IDs, then you can just put all the Ancestor IDs in the array. Otherwise (and only in the fixed hierarchy) you could prefix each ID with its record type - but that starts making it too blurry in my opinion.

SQL Server has a native Hierarchy ID data type that gives you a few convenience functions, but it is not mapped in Entity Framework so if you use EF you may prefer to just use a normal string.

Querying

In order to query the database you need to be able to search on Hierarchy IDs so ensure there is an index on the field for performance. Next you need to know which Hierarchy IDs a user is allowed to see.

In the case of a relational database you have a couple of options;

- If a user will only have access to a few Hierarchy IDs, then you can simply have those on listed on whatever user object (such as a ClaimsPrincipal) you are passing around in your code and you can then do some SQL along the lines of

SELECT FROM xx WHERE HierarchyID LIKE "123/23%" OR HierarchyID LIKE "516/67/43/109%". If you have many Hierarchy IDs per user then this will end up with a lot ofORstatements which can really hurt performance, so be careful. - If a user has access to many Hierarchy IDs it may be better to maintain a Hierarchy ID table in the database, with each row having a user ID and a Hierarchy ID and then

INNER JOINorAPPLYto that table in your query.

Just be mindful that if a user is allowed two Hierarchy IDs where one is a subset of the other, you will get duplicate records so you need to either useDISTINCTor remove such “duplicates” from the User-HierarchyID table beforeJOINing.

In the case of a document database that doesn’t support JOINs your only option is to keep that list of allowed Hierarchy IDs or Ancestor IDs and then use OR statements.

Mutability of the hierarchy

Some hierarchies are essentially immutable, others can change at times. For example, in the example above with customers and projects, it is exceedingly unlikely that a customer will move between resellers or a project will move between customers. In that scenario you can probably treat the Hierarchy ID as write-only and just set it once when you create the records. In the rare circumstance where you may have to change it, you can deal with that as a one-off and handle it manually.

Organisation hierarchies, in particular, have an annoying habit of changing over time. If someone’s manager changes, you have to update the Hierarchy IDs all the way down the tree. Depending on the potential size of the tree and your security requirements, this may be done in different ways. Bear in mind that when the CEO of a 100,000 person company changes, that’s a lot of records to update. In most scenarios you can just have a simple function that recurses through all the affected records and updates each one in turn. You may implement this at the database level or in application code, depending on your requirements. In a relational database you may be tempted to wrap this entire thing in a transaction, but be mindful that this may escalate to a table lock, which may effectively lock your whole system up. Alternatively, updating each record in turn may mean that for a few minutes (for a very large change) some users will see a mixture of the records they used to be able to see and the records they are going to be able to see. The user should never see records they weren’t meant to see; it may just take a few minutes to remove all the records they used to be able to see and add all the new records. Users may also need to re-login if you are caching their list of allowed Hierarchy IDs in a session object of some kind. Mostly, these changes are infrequent - at least changes that affect many records - so it’s usually not something to worry too much about, as long as you understand it for your system.

Ease of Writing vs ease of Reading

When you implement a Hierarchy ID, you are making it more complex to write data; Whenever you add a node in the hierarchy you now have to set it’s Hierarchy ID. If your tree is mutable, you also need to handle updating the Hierarchy IDs of all children whenever nodes are moved - something that can take considerable time and capacity if a high-level node is moved. Similarly, you may need to write code to maintain a list of “allowed hierarchy IDs” per user. In other words, Hierarchy IDs adds extra complexity to your system.

On the other hand, once Hierarchy IDs are in place, your data filtering/security code becomes much easier to write and your database queries will be much more performant.

Whether Hierarchy IDs are right for a given solution will, as always, depend on the needs of that system. Some of the key indicators that you may need it are;

- Deep hierarchies with access rights determined at multiple levels

- Large data sets in a hierarchy

- Self-referential hierarchies with access rights set at arbitrary levels (think pretty much any organisational hierarchy with scope-of-control security)

Hierarchical Configuration

It is a common requirement to have Hierarchical Configuration where a certain setting is different for a certain part of the tree. For example, you may have some settings that only apply to a particular Reseller, Customer or even Branch etc.

If you are already implementing Hierarchy IDs in the form of a delimited string, you could have a simple Configuration table that has the Key, the Value and the Hierarchy ID it applies to. When you want to find the value for a particular Hierarchy ID for a particular node, you can recursively search for a configuration setting that matches the node’s Hierarchy ID, or it’s parent or the grand parent etc, all the way up to the root. This is obviously not very efficient to query so you would need to cache it (or keep the whole thing in memory if possible), but it makes it very easy to model and extend.

What you really want is something like (pseudo code)

SELECT Value from Config WHERE

Config.HierarchyID = SUBSTRING(node_hierarchy_id, LENGTH(Config.HierarchyID))

You may well be able to write a SQL statement something like that, though it will definitely use a table scan - so still cache it.

In the case of document database with an array of Ancestor IDs, you’d need to ensure that the Ancestor ID array on the node is sorted by descent level so that you can look for configuration values in the right order (by walking up the tree).